JCR Misconduct Policies: A Note from the Policy Board

Over the last five years, the Policy Board of the Journal of Consumer Research has dedicated significant efforts to enhance the Journal’s procedures for investigating and addressing issues of research misconduct. Our goal has been to develop policies that strike a delicate balance between ensuring the scientific integrity of published work and safeguarding the rights to due process of authors subjected to allegations of research misconduct.

It is the Journal’s responsibility to implement mechanisms to detect and address instances of research misconduct. At the same time, given that charges of research misconduct are among the most serious allegations that can be leveled against any scholar, we approached this task with the understanding that improper handling of such cases can have catastrophic consequences not only for the accused individual’s career but also for the integrity of the field as a whole.

The purpose of this communication is two-fold: first, to describe the evolution of the policy that emerged from our efforts, and second, to share the findings of a recent survey soliciting feedback on the efficacy of the current policy. Recognizing that addressing issues of research misconduct necessitates a concerted effort from all stakeholders—journal authors, reviewers, editors, publishers, other researchers—we hope that this communication will foster an open dialogue about how the field and the Journal can more effectively address issues of research integrity moving forward.

The Policy

In recent years, concerns over research integrity have taken center stage across various social sciences. These concerns arose from questions about the replicability of published findings, documented cases of outright scientific fraud, and widespread coverage of such incidents in the press and in various social media. Collectively, these have fostered an atmosphere of skepticism about the validity of many scientific publications and about the efficacy of the standard peer-review system as the primary mechanism for ensuring scientific validity. At the same time, there have been growing concerns that the zest for more careful checks and balances may have veered into excessive territory, producing a culture of academic vigilantism that could unintentionally victimize the innocent. Left unchecked, this trend risks suppressing the spirit of exploration and discovery that is essential for the advancement of knowledge.

It was against this background that in 2019, working with the editors, the Policy Board undertook an overhaul of the Journal’s policies for research transparency and misconduct. Prior to 2019, the task of investigating issues of misconduct was primarily shouldered by the JCR editors, which added a layer of responsibility to the position that went well beyond making editorial judgments on manuscripts. In an effort to relieve this added burden on the editors and standardize the handling of cases of potential research misconduct, a revised misconduct policy was implemented in 2020 that moved most of this responsibility to the Policy Board, with the most recent revision being published in May 2023.

The essence of the policy is straightforward. When a complaint is received by the Journal, the editors are asked to make an initial judgment as to whether it involves possible misconduct. To aid the editors in making this initial determination, the manuscript’s authors are initially informed of the complaint, and are asked to provide information (e.g., clarifications, additional methodological details) that might help resolve the issue without further investigation. If this initial exchange is seen as insufficient to address the issues that are raised, it is then forwarded to the President of the Policy Board who may appoint an independent ad hoc investigatory committee of volunteer scholars with no conflict of interest with the authors or claimant. The role of this investigatory committee is to make a recommendation about the merit of the complaint and, in some cases, suggest a remedy (e.g., published correction or retraction).

This investigation is conducted in strict confidentiality. The complainant will, however, be asked to identify themselves to the President of the Policy Board and/or the chair of the investigatory committee in order to preclude conflicts of interest and to ensure accountability.[1] After their investigation is completed, the investigatory committee submits a report to the Policy Board, which then makes a decision about what to do about the case (e.g., retraction, sanction).

Under the policy, editors and the President of the Policy Board are given discretion to decide whether to proceed with an investigation, and the form it can take. While not formally stated, the standard of evidence to establish guilt in a case of misconduct is presumed to be very high for a reason that should be evident: the cost of mistakenly finding an author guilty of fraud when none existed far exceeds that of letting an article stand whose findings are later found to be in doubt. As such, the editors and the President of the Policy Board are entrusted with the responsibility of proceeding with investigations only if there is a reason to believe that further investigation is warranted.

Reactions to the Policy

After its release, we received no shortage of reactions to the policy: Some worried it may be insufficiently protective of the innocent, others saw it as insufficiently protective of attempts to uncover misconduct. One perspective was that an accusation of misconduct is extremely serious, yet the policy affords few of the protections that defendants normally enjoy in criminal or civil proceedings, such as a right to face witnesses, and there are no repercussions for false accusations. Others, however, offered the contrasting view that broad powers of investigation (including strict anonymity of claimants) are necessary to overcome the natural reluctance of journals and publishers to find fraud in the content they publish.

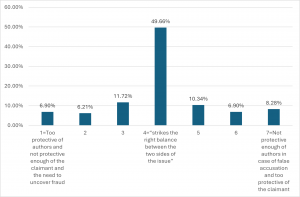

To obtain a broader view of reactions to the policy, in January we conducted an email survey of 220 current members of the JCR editorial board, associate editors, and editors—a group that represents many of the major thought leaders in our field. Participants were asked two questions. The first one was to rate on a 1-7 scale the degree to which they believed the current policy adequately balanced the need to uncover misconduct with the need to protect authors from false charges, where 1 was, “Too protective of authors and not protective enough of the claimant and the need to uncover fraud,” and 7 was, “Not protective enough of authors in case of false accusations and too protective of the claimant.” The second was an open-ended question that invited respondents to suggest changes or amendments to the policy if they found the policy inadequate. From this initial sample of 220, 145 responded to the ratings question, and 79 provided open-ended comments.

The results, shown in Figure 1, indicated that the current policy appears to be effective in balancing the two opposing perspectives. Half (49.7%) of the respondents provided a rating of 4 on the scale, which was defined as “strikes the right balance between the two sides of the issue.” Moreover, the other half of ratings were equally balanced between those who felt it could be more forceful in protecting authors (25.5%) and those who felt it could be more forceful in protecting claimants or attempts to uncover fraud (24.8%).

FIGURE 1

HISTOGRAM OF SURVEY RESULTS (N=145)

This balance was mirrored in the open-ended responses. While some felt the policy did not go far enough to protect the rights of the accused, an equal number felt it was not aggressive enough in allowing the discovery of fraud or misconduct. For example, the most common topic of discussion was whether claimants had a right to anonymity. Among the 79 individuals who responded, 30 explicitly commented on this issue, and among these, half (15) believed that the accused have the right to face their accusers, while half (15) believed anonymity must be honored at all costs—at least in the initial complaint.

Our Take, and Next Steps

We see the findings of the survey as delivering a mix of positive and negative news for both the Journal and the field. On the one hand, it is reassuring that the policy seems to occupy a “sweet spot” between the conflicting needs to protect authors while also facilitating the detection of fraud and misconduct and providing adequate protection for claimants. On the other hand, the evident polarization of opinions revealed by the survey is somewhat unsettling. There remains a substantial ideological divide on how best to manage research integrity issues within the field.

To this end, we hope this note will encourage the start of an open dialogue about how, as a journal and field, we can enhance trust in the integrity of published research. As this discussion evolves, readers should be reminded that while effective journal misconduct policies undoubtedly contribute to fostering research integrity, their effectiveness remains limited to serving as a final recourse in addressing problems when they arise. We see value in a more forward-looking approach that emphasizes the implementation of incentives that encourage ethical research practices, thereby addressing problems at their source before they manifest rather than reacting retrospectively.

These are undoubtedly difficult problems, but we maintain the belief that they are not insurmountable. Despite encountering diverse perspectives on how to improve JCR’s misconduct policy, we perceive the passionate expression of these views as a positive indicator. As we strive to address these challenges, we are committed to collaborating with the JCR community, recognizing that collective efforts are essential for progress. Ultimately, we share common goals. We look forward to receiving the community’s input and suggestions.

[1] Under COPE 2013 guidelines, journals are advised to accept anonymous complaints. The guidelines, however, do not address preservation of anonymity during the course of any subsequent investigation, when the identity of an accuser may be material (e.g., a claim of witnessing data fabrication).