How Do Brand Leaders Become Charismatic?

In a recently published Journal of Consumer Research article, Verena E Wieser, Marius K Luedicke, and Andrea Hemetsberger explain how brand leaders acquire “charismatic authority” in the marketplace. In their study, they identified a social mechanism in which brand leaders, consumers, and critics engage each other in dramatic public controversies over key issues such as justice, sustainability, or individual freedom. Here, the authors explain how this mechanism they call “charismatic entrainment” works and what it means for brands and their leaders.

How do brand leaders such as Vogue’s Anna Wintour or Tesla’s Elon Musk induce awe and inspiration among millions of consumers? How do they manage to transform ordinary consumers into eager followers who not only consume their brands, but also promote them, invest in them, and publicly defend them against criticism?

How do brand leaders such as Vogue’s Anna Wintour or Tesla’s Elon Musk induce awe and inspiration among millions of consumers? How do they manage to transform ordinary consumers into eager followers who not only consume their brands, but also promote them, invest in them, and publicly defend them against criticism?

Much has been written about charismatic political, religious and company leaders such as Donald Trump, creationist Ken Ham, or Steve Jobs, and what sets them apart from less extraordinary leaders. One key explanation is that they possess certain individual qualities, such as extraordinary skills, aesthetic vision, authenticity, a certain appeal, or even certain bodily features. However, the question that we found most fascinating was not who they are, but how they interact with consumers to recommend themselves, and eventually become accepted by a broader public as charismatic leaders.

To find out how brand leaders gain charismatic authority in the marketplace, we conducted an in-depth interpretive case study of Heinrich Staudinger, the founder and CEO of Austrian sustainable footwear brand Waldviertler. Between 2012 and 2017 Staudinger sparked five intense public debates where he passionately defended his iconic “Savings Club” against the Austrian finance market authorities (FMA). Staudinger had founded the Savings Club in 1999 to borrow money from committed customers in exchange for interest. In 2012, however, the FMA declared his Savings Club illegal and ordered Staudinger to repay the 2.8 million euros he had borrowed. Staudinger eventually lost the legal battle with the FMA, but he was able to keep the Savings Club under special conditions, massively expanded awareness and sales of his Waldviertler brand, and became widely known as a charismatic “financial rebel”. We conducted interviews with Savings Club consumer-investors, ordinary Waldviertler customers, journalists, and Staudinger himself. We collected an extensive set of archival data from the brand’s website, newspapers, and social media platforms, and participated in Waldviertler events.

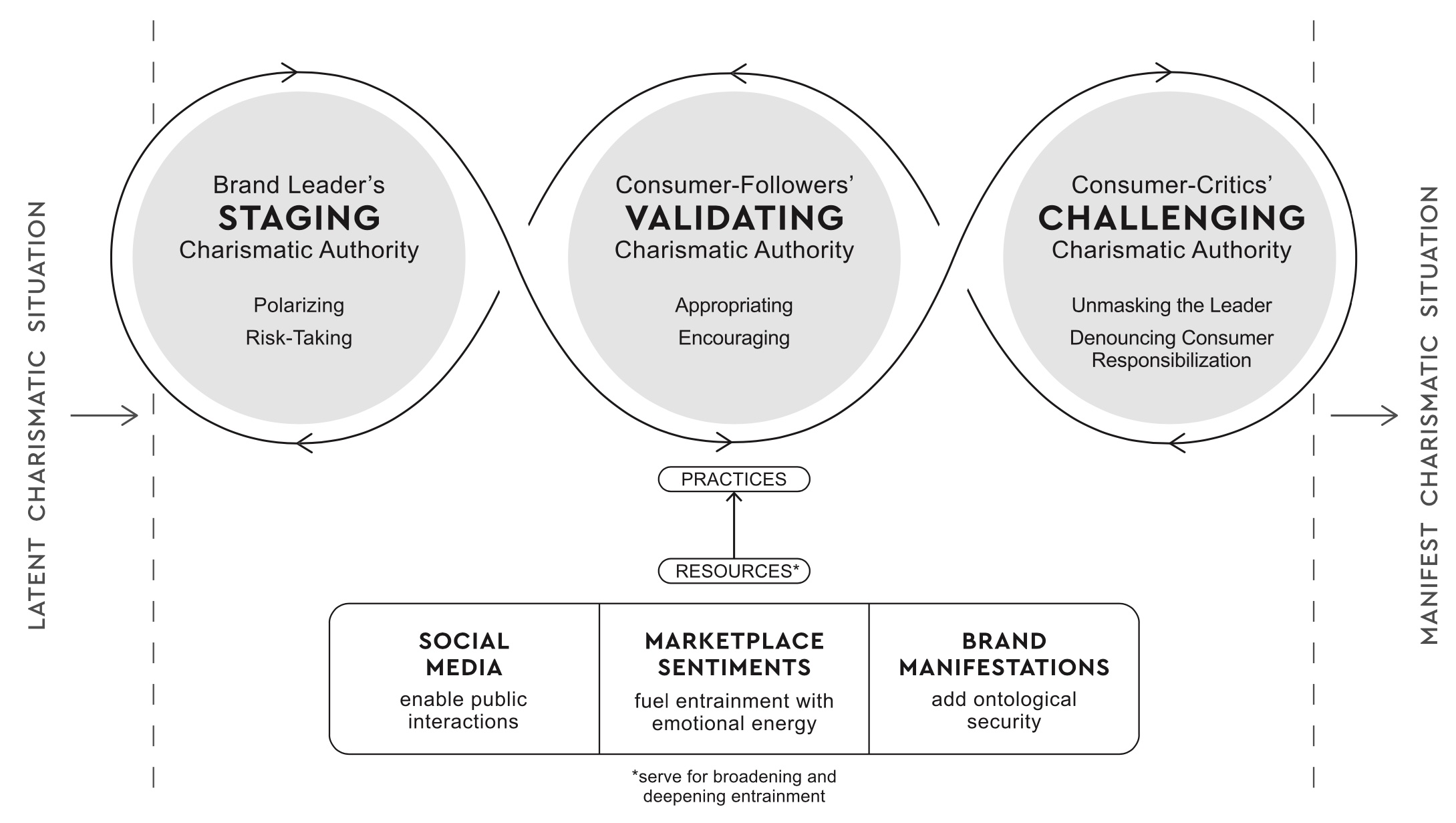

Our analysis revealed a sociocultural mechanism that we call “charismatic entrainment” (see figure). The mechanism involves three interactive practices we call staging, validating, and challenging charismatic authority. We adopted the entrainment idea from physics and biology to convey how a brand leader (attractor system) temporarily synchronizes previously disjointed elements such as consumers, critics, journalists, brand manifestations, venues, emotions, and pressing societal concerns to spark intense, public charisma co-creation episodes.

When staging charismatic authority, brand leaders recommend themselves to consumers as charismatic leaders. To show that they possess this quality, leaders sharply delineate an existing and apparently doomed future scenario against their own more promising future vision. Then, and importantly, brand leaders take significant personal risks to demonstrate their ability and determination to realize this alternative future scenario. Without this risk-taking, their words might be just empty marketing talk, but with it, consumers get inspired.

Consumers validate brand leaders’ staging efforts in two ways. They inwardly appropriate the leader’s bold risk-taking approach, sometimes leading to followers also becoming a bit more daring. Then they outwardly encourage leaders through buying products, for example, defiantly investing in their brands, writing complaint letters to opponents, participating in activist action, and, not least, supporting, defending and encouraging them on social media.

Prior studies have paid relatively little attention to the aspiring leaders’ critics. But for market—based charisma co-creation, they are essential. Consumer critics and other opponents contribute to enmeshing consumers and leaders deeper into charisma co-creation through publicly challenging brand leaders’ claims to charismatic authority, trying to protect vulnerable consumers from their seduction and exploitation efforts. Yet, in so doing, critics often unintentionally motivate brand leaders to intensify their staging, consumer-followers to increase their external validation, and journalists to cover the conflict even more. Thus, consumer critics themselves become entrained, fueling instead of mitigating charisma co-creation.

We also found that charismatic entrainment relies on three entrainment resources, i.e., brand manifestations, marketplace sentiments, and social media. In the article, we explain how leaders, followers, and detractors use these three resources in different ways and to achieve their respective goals.

Our study shows that these market-based interactions can have far-reaching consequences for leaders and their brands. Most notably, in our case, it led to skyrocketing demand for the Waldviertler brand, to more and more consumers investing in the brand’s Savings Club (despite the risk of losing it all), and to Heinrich Staudinger becoming established as a charismatic authority in matters of crowdfunding and sustainable business.

Future research will have to show under which conditions charismatic entrainment fails (we have some clues here), how market-based charismatic authority is lost, whether validating charismatic leaders can have unintended consequences for consumers, and how dangerous charismatic brand leaders can be to society if they use their influence for the wrong cause.

Read the full paper: