Why Consumers Value Effort in Caregiving

Products designed to make caregiving easier may come with a cost. As Ximena Garcia-Rada and her co-authors argue in their recent JCR paper (one of the Editor’s Choice papers in the April 2022 issue of JCR), consumers may feel they have not exerted enough effort.

Caring for the people we love is important and meaningful. But it also entails a lot of hard work. Help does exist to make caregiving easier: people can pay for services like nannies or premade meals for family dinners, or products like slow cookers or even robocribs to soothe babies. Yet caregivers may often fail to take advantage of these shortcuts. Our recent research suggests one reason why: by using such products and services to care for others, consumers feel they have not exerted enough effort, because effort is an important part of how caregivers show their love.

Caring for the people we love is important and meaningful. But it also entails a lot of hard work. Help does exist to make caregiving easier: people can pay for services like nannies or premade meals for family dinners, or products like slow cookers or even robocribs to soothe babies. Yet caregivers may often fail to take advantage of these shortcuts. Our recent research suggests one reason why: by using such products and services to care for others, consumers feel they have not exerted enough effort, because effort is an important part of how caregivers show their love.

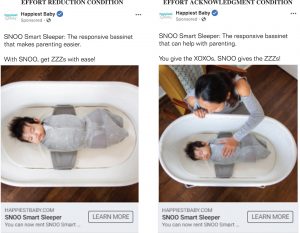

Consider one example of the complicated relationship between effort and caregiving: the SNOO Smart Sleeper. Designed by pediatric expert Dr. Harvey Karp, this high-tech bassinet automatically rocks crying babies back to sleep. But despite the benefits it can bring to both fussy babies and sleep-deprived parents, a significant proportion of the social media posts we examined on two news articles about the SNOO were negative. Many of these comments suggested that parents who would use the SNOO were lazy and detached. This seemed to reflect the commenters’ belief that proper caregiving should be effortful, and that SNOO users were taking an unacceptable shortcut.

So people judge others who use caregiving shortcuts, but how do they feel about using such products and services themselves? Across a series of experiments, spanning different caregiving tasks and relationships, we consistently found that consumers also believed that they should put effort into caregiving. They preferred more effortful options for caregiving over products and services that could make taking care of others easier, and when they did opt to put less effort into caregiving, they felt like they were doing a worse job. For example, our participants felt like better caregivers when they sent a hand-drawn card to their grandparents than a preprinted card, and they preferred to bake cookies for their relationship partner from a hand-stirred mix than bake the exact same cookies using frozen dough.

The reason why consumers choose to put effort into caregiving and feel bad when they don’t is that effort is seen as an important part of showing love, and effort-reducing products can make it harder for users to show how deeply they care about the other person. Consumers are especially likely to prefer effortful options for caregiving when signaling love is most important: for instance, when they are caring for another person versus performing self-care, or when they are caring for someone they are particularly close to.

Given these findings, what should marketers do to encourage people to use effort-reducing products and services? One option is to make these products more appealing by acknowledging the effort that consumers put into caregiving rather than emphasizing how these products require less effort. We partnered with Happiest Baby, the manufacturer of the SNOO, and conducted an experiment on social media to test which messages work best. We found that twice as many people clicked on an ad that acknowledged parents’ caregiving efforts (“You give the XOXOs, SNOO gives the ZZZs!”) than one that focused on how the SNOO can make parenting easier (“With SNOO, get ZZZs with ease!”).

Our work suggests that marketers should tread carefully when advertising products and services that can make caregiving easier. But it also sheds light on why people, especially parents and other dedicated caregivers, can feel so overwhelmed these days. Caregivers may avoid many products that could make their lives easier, and feel bad when they do use them, because they believe putting in effort is necessary to show how they feel about the people they love.

Read the full paper:

Consumers Value Effort over Ease When Caring for Close Others

https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucab039