Consumption under Fragmented Stigma

Twenty years ago, Steven Kates characterized Toronto’s gay men in the Journal of Consumer Research as a subculture that was substantially “stigmatized in its history of oppression and marginalization” (2002, 383). In his article, Kates documented how gay consumers used brands and consumption in the late 1990s to avoid, cope with, and resist an anti-gay stigma that, despite the achievements of the post-Stonewall-generation, still loomed large within society (Kates 2002, 2004). The gay subculture was therefore the only “safe place” (Kates 2002, 386) where gay men could obtain sociability, sex, and partnership, and collectively celebrate their unique fashion styles, musical tastes, or expressive genres like drag without facing the outright discrimination they would face “in the straight world” (389).

A lot has happened since the publication of Kates’ work, not only in civil law (e.g., same-sex marriage), but also in terms of the visibility and representation of LGBTIQ+ people in society and popular culture (e.g., openly gay politicians, celebrities, or sports idols). Yet, despite these substantial social changes, the subcultural approach has remained the dominant theoretical approach in socio-cultural consumer studies on gay men’s consumption and identities (Coffin, Eichert, and Noelke 2019).

To better understand the impact of these profound societal changes on consumers, consumer culture theorists Christian A. Eichert of Goldsmiths, University of London and Marius K. Luedicke of Bayes Business School conducted a multi-method, interpretive study of gay men in Germany. They focused on the social representations, collective identities, and consumption strategies that have emerged since the stigmatization of gay men in German society has, on average, declined. Over a period of seven years, the authors explored how gay teachers, civil servants, students, and soldiers, among others, see themselves as members of a gay community and broader society, how they are seen by others in society, and how this shaped their consumption behaviors.

To better understand the impact of these profound societal changes on consumers, consumer culture theorists Christian A. Eichert of Goldsmiths, University of London and Marius K. Luedicke of Bayes Business School conducted a multi-method, interpretive study of gay men in Germany. They focused on the social representations, collective identities, and consumption strategies that have emerged since the stigmatization of gay men in German society has, on average, declined. Over a period of seven years, the authors explored how gay teachers, civil servants, students, and soldiers, among others, see themselves as members of a gay community and broader society, how they are seen by others in society, and how this shaped their consumption behaviors.

As a subcultural position could no longer be taken for granted, Eichert and Luedicke drew on social representations theory to map the shifting, and partially competing, anchorings, objectifications, and representations about (and among) gay men in German society.

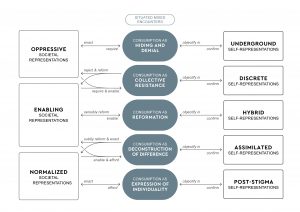

Their study shows that since about 1969, societal representations of gay men have shifted from predominantly oppressive (total stigma), through oppressive and enabling (dominant stigma), to oppressive, enabling, and normalized representations of gay men (fragmented stigma). Alongside these societal shifts, the gay subculture itself disintegrated into five distinct, and partially competing, sub-groups which the authors call underground, discrete, hybrid, assimilated, and post-gay social groups (see figure for an overview).

- Underground gay men predominantly face oppressive societal representation in their social surroundings. These men are still not afforded the social space to exist as openly gay. For them being ‘outed’ would result in exclusion from their families and circles of friends, job loss, or even physical violence. Underground gay men therefore avoid market offerings that are considered stereotypically gay, such as skinny jeans, golden Adidas sneakers, or plucked eyebrows, and consume in deliberately “straight” and “invisible” ways.

- Discrete men face both oppressive and enabling societal representations in their surroundings. They enjoy enough legal protection to be openly gay. They feel tolerated, but not respected in society, and wish to protect their distinct gay lifestyle and subcultural heritage against mainstream appropriation. Discrete gay men therefore prefer gay neighbourhoods, expressive fashion styles, explosive pride parades, and stereotypical gay identities that have characterised members of the “gay subculture” or “gay community” not only since the 1980s.

- Hybrid gay men live in an innovative space in between gay and straight worlds. As they face predominantly enabling societal representations in their lifeworlds, they confidently inject gay consumption practices into heteronormative spheres, but also heteronormative practice into gay spheres, to reform acceptabilities on either side. Gay football fan clubs or queered wedding ceremonies are prime examples.

- Assimilated gay men face both enabling and normalized representations in their surroundigns. Thus, they seem fully accepted by their families, friends, and workplaces, but only under the condition that stay away from (discrete) gay consumption practices and identities and de-politicize their sexuality. For broader society, these men are respected as “completely normal” as long as they assimilate into a heteronormative mainstream culture and do not act up.

- Post-gay men are the only entirely liberated group among the five as their families, friends, and work colleagues exclusively hold normalized representations of gay men. Post-gay men not even face mere tolerance, but are fully respected. They live and work among others who show respect for human diversity. Post-gay men can therefore consume to freely express themselves and enjoy the occasional gay party or pride parade as a consumption spectacle, rather than a political statement or identity resource.

Figure: Consumption under Fragmented Stigma

Under the dominant stigma conditions that were captured in earlier studies, gay men could strategically consume to avoid stigma, and organize to collectively resist and cope with it. This new study shows that where stigma has fragmented, historically stigmatized social groups are able to cultivate consumption strategies that range from consumption as hiding and denial through consumption as deconstruction of differences to consumption as expression of individuality.

The research also documents that the stigmatization of homosexuals in progressive societies is not yet a thing of the past – although some studies claim the contrary. Underground gay men, in particular, still face substantial oppression and have to hide and deny their homosexuality in their everyday lives. Discrete men still face substantial stigma in and beyond the marketplace and continue to collectively resist discrimination through a continuation of their subcultural existence. Thus, despite overall societal progress towards destigmatization, many non-heterosexual men still perceive their sexual orientation, and the identities that are ascribed to or derived from it, as a life-defining characteristic.

Last, but not least, Eichert and Luedicke’s study sheds empirical light on the residual vulnerability that all gay men in their study share, including those who feel no longer stigmatized. When gay men learn about anti-gay hate crimes, or right-wing politicians’ instrumentalizing anti-gay sentiments for political gains, they are reminded that, despite all progress, they are not entirely equal yet.

Read the full paper:

Almost Equal: Consumption under Fragmented Stigma