The Consumption of Crowdfunding

Reward-based crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter and Indigogo are wildly popular around the globe. Every year, consumers use these platforms to transfer billions of dollars to help entrepreneurs and artists develop market innovations. Strangely, though, these consumers obtain no financial benefits from these producers, no legal guarantee that their money will be used aptly, and no reimbursement options. These unfavorable conditions led authors Andre F. Maciel (University of Nebraska—Lincoln) and Michelle F. Weinberger (Northwestern University) to ask in their most recent JCR article why so many consumers contribute to crowdfunding. In short, how is crowdfunding so successful?

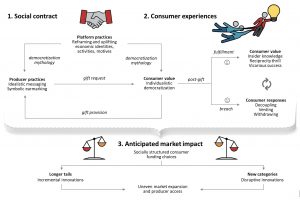

The authors collected qualitative data from crowdfunding consumers, producers, and platforms to reveal the sociocultural underpinnings of this funding model. They found that platforms do more than creating a technical infrastructure for consumers to transfer money to producers: they also create a mythological foundation. Through storytelling, platforms cast crowdfunding as a route to create a more democratic society in which ordinary people (vs. banks and wealthy investors) can decide and finance the products that should exist in the market. Consumers then gladly gift their money to entrepreneurs and artists fundraising on these platforms, financing their innovation ideas interest-free.

Instead of a legal contract, crowdfunding platforms establish with consumers a “social contract” based on noble collective goals and intangible returns. In exchange for their gifts to support market democratization, these consumers derive four unique forms of intangible value. First, they get to express their tastes by selecting the innovations that they deem worthy of existing in the market—an opportunity that stands out from their conventional experiences as mass consumers elsewhere. This opportunity is even more significant because their tastes are often niche, patterning the immaterial value of “individualistic democratization.” Second, as producers provide updates on their projects’ progress, consumers relish peeking behind the scenes of the entrepreneurial journey, acquiring the immaterial value of “insider knowledge” in their oft-niche areas of interest. Third, consumers derive excitement from betting some money on the ideas of typically unknown producers. When these producers fulfil their projects and send their supporters some reward—typically symbolic tokens and an early version of the crowdfunded project—these consumers experience “reciprocity thrill.” Finally, crowdfunding consumers derive the immaterial value of “vicarious success”: the experience of getting a flavor of the glow of successful entrepreneurship while taking on little risk.

Nonetheless, the authors also articulate an important limitation of reward-based crowdfunding. On the one hand, crowdfunding propels many projects that would not receive bank loans or venture capital for lacking a clear profit potential. On the other hand, crowdfunding tends to attract a specific segment of consumers: well-educated professionals involved in industries focused on producing knowledge, technology, and entertainment. These consumers tend to support projects they deem “cool.” They channel money to innovations that match their tastes, hardly ever picking projects based on the potential to broadly enhance social equality or welfare. Thus, crowdfunding fosters the market, but not as democratically as it seems.

Crowdfunding has become a relevant branch of the digital economy. Today, it is used not only by upcoming entrepreneurs and artists. Universities, museums, churches, and media organizations (e.g., NPR, Wikipedia, and The Guardian) regularly run campaigns to raise money from large numbers of people to create and enhance their market offerings. As such, this new research article is timely in three main ways: It sheds light on the consumer appeal of this funding model; it brings into relief the role of platforms in shaping the meanings of the digital economy; and it calls into question these businesses’ egalitarian claims.

Read the full paper:

Crowdfunding as a Market-Fostering Gift System

Andre F. Maciel and Michelle F. Weinberger

Journal of Consumer Research, ucad052, https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucad052